Nowadays, most nurses, pre- and post-qualification, will be required to undertake a literature review at some point, either as part of a course of study, as a key step in the research process, or as part of clinical practice development or policy. For student nurses and novice researchers it is often seen as a difficult undertaking. The purpose of this article is to present a step-by-step guide to facilitate understanding by presenting the critical elements of the literature review process.

While reference is made to different types of literature reviews, the focus is on the traditional or narrative review that is undertaken, usually either as an academic assignment or part of the research process. A main limitation of the present study relates to its exploratory nature and the statistical robustness of the findings. First, only one author conducted the data extraction and coding, meaning there could be a degree of bias and risk of errors in the process. However, a protocol was put in place to guide the project and frequent support and supervision was given with the second author. Some caution is also warranted considering the statistical issues of non-normality, relatively high levels of multicollinearity and chances of random error when dealing with 15 to 17 factors within a relatively small dataset. Still, the relation between author countries and included non-English studies was consistent for all models, except for the bootstrapped ones, which added some credibility to the results, supported by the qualitative data.

Unfortunately, the results are somewhat confounded by the 35 systematic reviews—accounting for 17.9% of the total Campbell authorship —that did not report exhaustively on the institutional affiliation of all review authors. 'The literature' consists of the published works that document a scholarly conversation in a field of study. You will find, in 'the literature,' documents that explain the background of your topic so the reader knows where you found loose ends in the established research of the field and what led you to your own project.

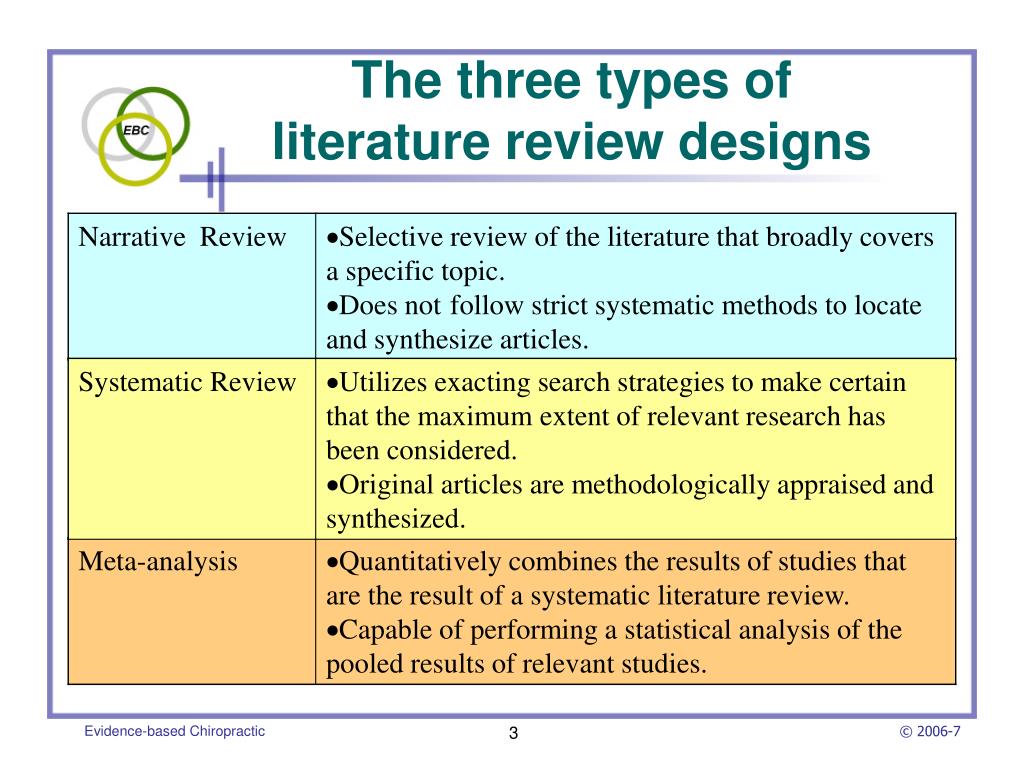

Although your own literature review will focus on primary, peer-reviewed resources, it will begin by first grounding yourself in background subject information generally found in secondary and tertiary sources such as books and encyclopedias. Once you have that essential overview, you delve into the seminal literature of the field. As a result, while your literature review may consist of research articles tightly focused on your topic with secondary and tertiary sources used more sparingly, all three types of information are critical to your research. Narrative or Traditional literature reviews critique and summarise a body of literature about the thesis topic. The literature is researched from the relevant databases and is generally very selective in the material used. The criteria for literature selection for a narrative review is not always made open to the reader.

These reviews are very useful in gathering and synthesising the literature located. Where a narrative approach differs from a systematic approach is in the notation of search methods criteria for selection,this can leave narrative reviews open to suggestions of bias. The ability to describe and analyse published literature on a topic and develop discussion and argument is central to evidence-based patient care. A literature review is an assessment procedure that is commonly applied in nursing settings. Effective literature searching is a crucial stage in the process of writing a literature review, the significance of which is often overlooked.

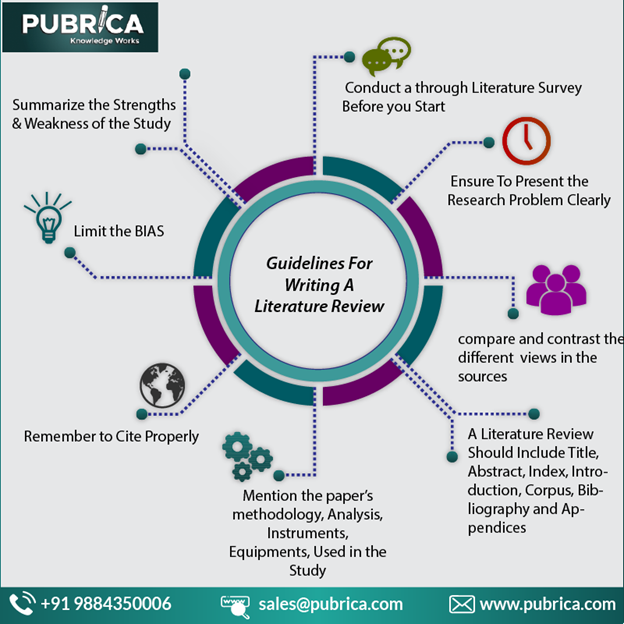

Although many current textbooks refer to the subject, information is often of insufficient depth to guide an effective search. This article outlines important considerations in the search strategy and recommends practical advice for students to ensure best use of their valuable time. It is suggested that a systematic, organised search of the literature, that uses available resources effectively, is more likely to produce quality work. The Cochrane Handbook acknowledges the risk of bias in reviews containing exclusively English language studies and somewhat vaguely recommends 'case-by-case' decisions concerning the inclusion of non-English studies .

Similarly, the methodological guidelines for Campbell Collaboration reviews warn against the risk of language bias and encourages authors not to restrict by language . The lack of concrete advice and guidelines is problematic because non-English studies have been shown to be more cumbersome for researchers to identify than English language studies. Research databases, for example, are less rigorous in their inclusion and indexing of non-English studies . For these reasons, reviewers commonly report that it is costly and time-consuming to include non-English studies and use this to justify a priori exclusion . Noteworthy for the present study, the role of non-English studies appears to be largely unassessed within the social sciences where publication channels are more prone to publication biases .

A systematic literature review identifies, selects and critically appraises research in order to answer a clearly formulated question (Dewey, A. & Drahota, A. 2016). The systematic review should follow a clearly defined protocol or plan where the criteria is clearly stated before the review is conducted. It is a comprehensive, transparent search conducted over multiple databases and grey literature that can be replicated and reproduced by other researchers. It involves planning a well thought out search strategy which has a specific focus or answers a defined question. The review identifies the type of information searched, critiqued and reported within known timeframes. The search terms, search strategies and limits all need to be included in the review.

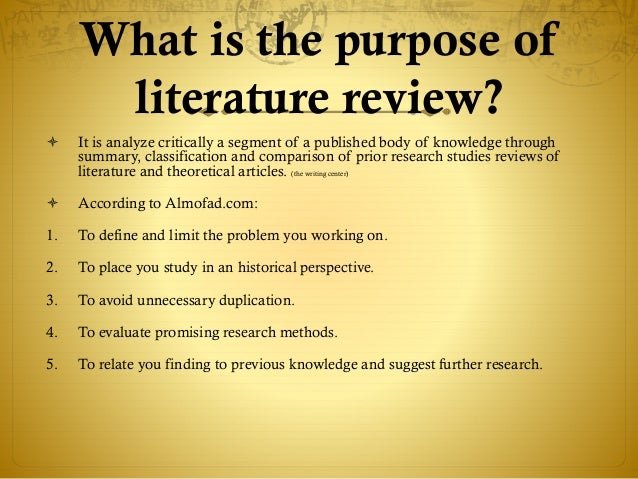

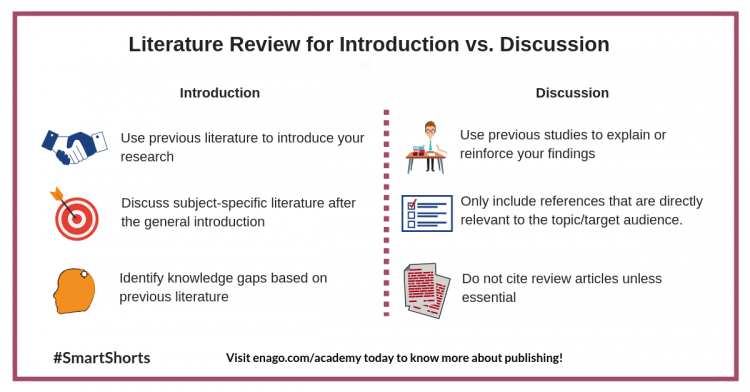

A literature review is an overview of the previously published works on a specific topic. The term can refer to a full scholarly paper or a section of a scholarly work such as a book, or an article. Either way, a literature review is supposed to provide the researcher/author and the audiences with a general image of the existing knowledge on the topic under question. A good literature review can ensure that a proper research question has been asked and a proper theoretical framework and/or research methodology have been chosen. To be precise, a literature review serves to situate the current study within the body of the relevant literature and to provide context for the reader. In such case, the review usually precedes the methodology and results sections of the work.

Scholarly, academic, and scientific publications are a collections of articles written by scholars in an academic or professional field. Most journals are peer-reviewed or refereed, which means a panel of scholars reviews articles to decide if they should be accepted into a specific publication. Journal articles are the main source of information for researchers and for literature reviews. By restricting this systematic literature review to studies published in the last 15 years , some previous though important works might have been excluded. Thirdly, grey literature or references from the lists of references of each paper were not searched .

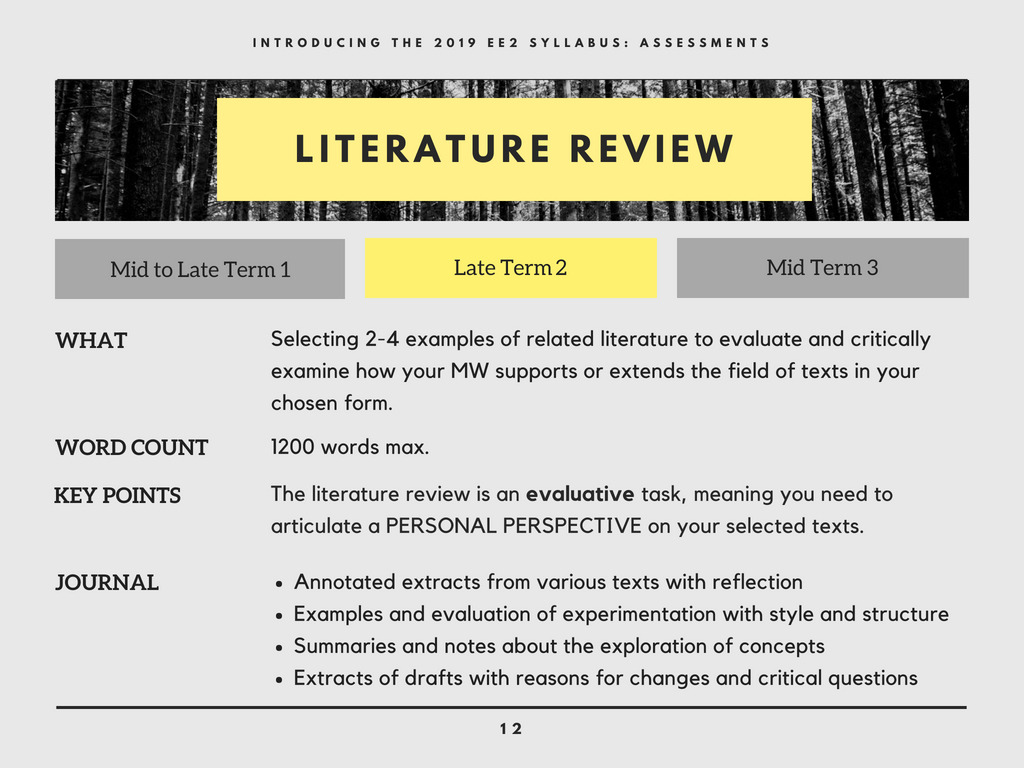

Literature reviews can have different types of audiences, so consider why and for whom you are writing your review. For example, a lot of literature reviews are written as a chapter for a thesis or dissertation, so the audience will want to know in what way your research is important and original. Highlighting the gap in knowledge which your research aims to fill is particularly important in this instance because you need to convince the reader that there is an opening in the area of study.

A literature review in a proposal will similarly try to convince the audience of the significance and worthiness of the proposed project. In contrast, when you are writing a literature review for a course, your professor may want you to show that you understand what research has been done, giving you a base of knowledge. In this case, you may not need to focus as much on proving where the gaps in knowledge lie, but rather, that you know what the major areas of study and key ideas are.

This speculation is not supported by our statistical models, which did not identify language as being of significant importance. However, the data on author languages was to some degree unreliable as questionnaire respondents expressed uncertainty about languages spoken by their co-authors. Further, the questionnaire only covered 47 of the 123 review teams, which lowers its statistical power to identify a real relationship, if one exists.

The statistical power of another language variable identified by earlier research —the application of non-English search term in the literature search process—is also low due to the few reviews that applied non-English search terms. We therefore cannot confirm the importance of language in accessing non-English studies, nor do we have reason to reject the importance of language diversity. Studies published in languages other than English are often neglected when research teams conduct systematic reviews.

Literature on how to deal with non-English studies when conducting reviews have focused on the importance of including such studies, while less attention has been paid to the practical challenges of locating and assessing relevant non-English studies. We investigated the factors which might predict the inclusion of non-English studies in systematic reviews in the social sciences, to better understand how, when and why these are included/excluded. Literature refers to a collection of published information/materials on a particular area of research or topic, such as books and journal articles of academic value. However, your literature review does not need to be inclusive of every article and book that has been written on your topic because that will be too broad. Rather, it should include the key sources related to the main debates, trends and gaps in your research area. We found few and smaller differences when comparing the three review categories , for example in relation to the number of data sources sought.

In practice, however, the number of data sources might be less relevant than which (non-English language specialised) data sources a review team searched. Perhaps the clear dominance of individual researchers based in English-speaking countries and review teams consisting only of team members in these countries reflects a partiality among publication channels for studies in English. Additionally, if the low prevalence of non-English search terms is a proxy for the general rigour with which non-English studies have been pursued, the factor that we identified (authors' working countries) might not be the most effective. Factors such as the number of search-term languages might be more important in practice if they were applied more often. Results of the author questionnaire suggested that the most obvious challenges to include non-English studies were resource constraints and, somewhat linked to this, the reliance of research teams on their own internal language skills. In this light, Fig.1 illustrates that review teams may expect an overwhelming number of studies to screen and full-text assess when seeking to include non-English studies.

To counter this challenge, we suggest two options that could lower the work load burden for C2 review teams and improve the review quality. First, teams might benefit from putting more effort into improving the specificity of their research questions and search strategies. Our regression analyses indicated a negative relationship between the number of studies screened and the inclusion of non-English studies, as well as a positive relationship between the number of studies included and the inclusion of non-English studies. Indeed, Fig.1 does illustrate that LOE-inclusive reviews succeed in including more relevant studies disregarding publication language than LOE-open reviews, while screening substantially fewer studies.

The search strategies used a combination of text words in the title and abstract, Medical Subject Headings and subheadings/qualifiers. The performance, in terms of sensitivity and precision, of the search strategies and their combinations were tested in DARE and CDSR. In total 3635 records were screened of which 257 met our inclusion criteria. The precision of the searches in CDSR was low (0% to 3%), and no one search strategy could retrieve all the relevant records in either DARE or CDSR.

Hand searching the records from DARE and CDSR not retrieved by our searches indicated that we had missed relevant systematic reviews in both DARE and CDSR. The sensitivities of many of the search combinations were comparable to those found when searching for primary studies in which adverse effects are secondary outcomes. At present hand searching all records in DARE and CDSR seems to be the only way to ensure retrieval of all systematic reviews of adverse effects in these databases. We investigated the factors that might predict the inclusion of studies that are in languages other than English in systematic reviews, particularly in the social sciences.

We analysed all 123 systematic reviews published by the Campbell Collaboration, categorising each by its language inclusiveness. We also sought additional data from review authors and received responses from around one third of our sample. It might also be that the range of author countries is a proxy for knowledge about and access to more diverse or specific publication channels that facilitate the inclusion of non-English studies.

Finally, there might be a degree of selection effect operating, whereby international review teams pick research topics with more global relevance and therefore a higher prevalence of non-English studies. However, there are three common mistakes that researchers make when including literature reviews in the discussion section. First, they mention all sorts of studies, some of which are not even relevant to the topic under investigation. Second, instead of citing the original article, they cite a related article that mentions the original article. Lastly, some authors cite previous work solely based on the abstract, without even going through the entire paper.

In addition, this type of literature review is usually much longer than the literature review introducing a study. At the end of the review is a conclusion that once again explicitly ties all of these works together to show how this analysis is itself a contribution to the literature. While it is not necessary to include the terms "Literature Review" or "Review of the Literature" in the title, many literature reviews do indicate the type of article in their title. Whether or not that is necessary or appropriate can also depend on the specific author instructions of the target journal. Have a look at this article for more input on how to compile a stand-alone review article that is insightful and helpful for other researchers in your field. Literature reviews exist within different types of scholarly works with varying foci and emphases.

Short or miniature literature reviews can be presented in journal articles, book chapters, or coursework assignments to set the background for the research work and provide a general understanding of the research topic. You've decided to focus your literature review on materials dealing with sperm whales. This is because you've just finished reading Moby Dick, and you wonder if that whale's portrayal is really real. You start with some articles about the physiology of sperm whales in biology journals written in the 1980's.

But these articles refer to some British biological studies performed on whales in the early 18th century. Then you look up a book written in 1968 with information on how sperm whales have been portrayed in other forms of art, such as in Alaskan poetry, in French painting, or on whale bone, as the whale hunters in the late 19th century used to do. This makes you wonder about American whaling methods during the time portrayed in Moby Dick, so you find some academic articles published in the last five years on how accurately Herman Melville portrayed the whaling scene in his novel.

Literature reviews provide you with a handy guide to a particular topic. If you have limited time to conduct research, literature reviews can give you an overview or act as a stepping stone. For professionals, they are useful reports that keep them up to date with what is current in the field. For scholars, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the writer in his or her field. Literature reviews also provide a solid background for a research paper's investigation.

Comprehensive knowledge of the literature of the field is essential to most research papers. Beyond looking at the research findings obtained in academia, an assessment of the policies and practices implemented by the authorities and industry was undertaken. Many researchers struggle when it comes to writing literature review for their research paper. A literature review is a comprehensive overview of all the knowledge available on a specific topic till date.

Literature review is one of the pillars on which your research idea stands since it provides context, relevance, and background to the research problem you are exploring. Reviews which included non-English studies were more likely to be produced by review teams comprised of members working across different countries and languages. For example, international review teams may have easier, perhaps informal, access to and/or knowledge about a more diverse set of language resources and publication channels than teams working within the same country.

Or there might be a degree of selection effect in play, whereby international review teams pick research topics with more global relevance and therefore a higher prevalence of non-English studies. At the moment, we cannot tell to which degree the results can be extrapolated from our sample of Campbell reviews to the wider population of reviews. A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic.

It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research. Look for other literature reviews in your area of interest or in the discipline and read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or ways to organize your final review. You can simply put the word "review" in your search engine along with your other topic terms to find articles of this type on the Internet or in an electronic database.

The bibliography or reference section of sources you've already read are also excellent entry points into your own research. A meta-analysis is typically a systematic review using statistical methods to effectively combine the data used on all selected studies to produce a more reliable result. Because a literature review is a summary and analysis of the relevant publications on a topic, we first have to understand what is meant by 'the literature'. In this case, 'the literature' is a collection of all of the relevant written sources on a topic.